Who’s history ?

https://share.google/zkeoSxGtQVnGA40aI

Telegraph (London) article by Andrew Graham Dixon, art critic, journalist, (2000)

‘“The historical novel has always been a literary form at war with itself. The very term, implying a fiction somehow grounded in fact — a lie with obscure obligations to the truth — is suggestive of the contradictions of the genre”’ (R.Lee, 2000, quoting Dixon).

Lee, however, countered by reminding his audience that Dixon’s claim can just as easily be said of something contemporary’. He asked his audience

to think of Trainspotting (1996) or Bridget Jones’ Diary (1996). No one think of these two books are true: ‘Yet no-one would bother to read them if they didn’t believe that they were in some way drawn from life.’ Lee claims this may be a ‘contradiction’ but ‘it’s an absolute fundamental — perhaps the absolute fundamental quality of art. Not just fiction, but sculpture, painting, poetry ….all art’. For Lee, in this sense ‘all art is, to use Dixon’s words “at war itself”’. For Lee, ‘It [historical fiction] seeks, at the same time, both accuracy and illusion. It is ludicrous to say this is only a defining characteristic of historical fiction — it’s a defining characteristic of all fiction’

Dreamtime stories explanation from Gemini AI . History or Understanding of the World

Dreamtime, also known as the Dreaming or Jukurrpa, is a foundational concept in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture, serving as a way to understand the creation of the world, the relationship between people and the land, and the interconnectedness of all living things. It is a rich tapestry of stories, beliefs, and practices passed down through generations, and it’s not a simple history or religion, but rather a way of life.

Here’s a breakdown of the Dreamtime:

- Creation Stories:Dreamtime stories explain how the world, including the natural world, humans, and animals, came to be. These stories often involve Ancestral Beings who shaped the land and created life.

- Spiritual and Moral Framework:The Dreamtime provides a framework for understanding the world, how people should interact with it, and the rules and customs that govern Aboriginal society.

- Interconnectedness:Dreamtime emphasizes the interconnectedness of all things, including people, the land, and the spirit world.

- Cultural and Religious Significance:The Dreamtime is central to Aboriginal spirituality, influencing their beliefs, rituals, and art.

- Living History:Dreamtime stories are not static narratives; they are living histories that are constantly being retold and adapted, with new generations adding their own interpretations and stories.

Key Concepts and Themes:

- Ancestral Beings:These are the spiritual entities who are believed to have shaped the land and created life.

- Songlines:Paths followed by Ancestral Beings, often representing sacred sites and routes across the land.

- Sacred Sites:Locations where powerful Ancestral Beings are believed to have dwelled or performed their creation work.

- Kinan:A system of kinship and responsibility that binds people to their community and to the land.

- Spirituality:The Dreamtime is deeply intertwined with spirituality, with Aboriginal people believing that their ancestors and spirits are still present in the land.

In essence, the Dreamtime is not a historical account in the traditional sense, but rather a way of understanding the world and one’s place within it. It is a complex and rich system of beliefs, stories, and practices that have shaped Aboriginal culture for thousands of years.

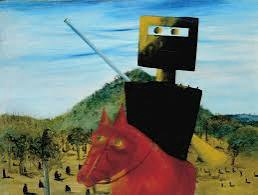

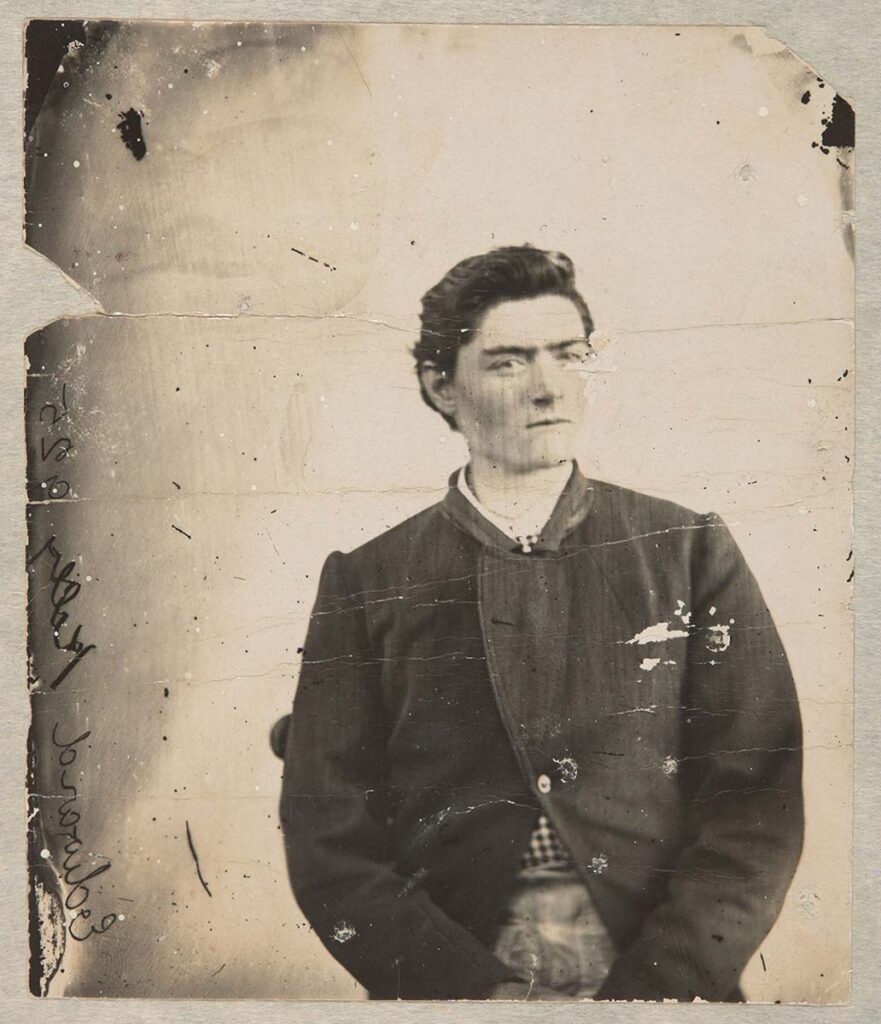

Nolan and Kelly

Australian artist Sidney Nolan painted numerous Ned Kelly works, beginning with his now-iconic 1946–47 series, which Nolan later said was inspired by “Kelly’s own words, and Rousseau, and sunlight”. The Jerilderie Letter in particular “fascinated [Nolan] with their blend of poetry and political engagement”.[46]

The Jerilderie letter

https://www.nma.gov.au/explore/features/ned-kelly-jerilderie-letter

Australian author Peter Carey has said the main lnfluences on his Booker Prize-winning novel True History of the Kelly Gang (2001) were the Jerilderie Letter, Nolan’s Ned Kelly paintings, and James Joyce.[48] Carey described Kelly’s voice in the Jerilderie Letter as that of an “avant-garde artist with hardly a comma to his name”, and in writing True History of the Kelly Gang, he aimed to recreate it. Of his first reading of the Jerilderie Letter, Carey said:

Somewhere in the middle Sixties, I first came upon the 56-page letter which Kelly attempted to have printed when the gang robbed the bank in Jerilderie in 1879. It is an extraordinary document, the passionate voice of a man who is writing to explain his life, save his life, his reputation … And all the time there is this original voice – uneducated but intelligent, funny and then angry, and with a line of Irish invective that would have made Paul Keating envious. His language came in a great, furious rush that could not but remind you of far more literary Irish writers.[49]